HALCYON DAYS

September 26 - Ocotober 31, 1999

Artwork of the Twenties, Thirties & Forties

By Frederick Dirnfeld, Joseph Newman and Ben Solowey

the worst of times. Hindsight and historical distance has not changed this view. In this exhibition, we explored the effect of these decades through the work of three artists. Ben Solowey

the worst of times. Hindsight and historical distance has not changed this view. In this exhibition, we explored the effect of these decades through the work of three artists. Ben Solowey , Joseph Newman

and Frederick Dirnfeld

did not know each other, yet they resonate with similarities throughout their lives and work. The art they created during this period is both of its time and outside of it, a paradox like the world they lived in.

, Joseph Newman

and Frederick Dirnfeld

did not know each other, yet they resonate with similarities throughout their lives and work. The art they created during this period is both of its time and outside of it, a paradox like the world they lived in.Solowey, Newman and Dirnfeld were not seduced by the streamline of the machine as many artists of the day. Their art identified with more tranquil and ordered times. While New York City, were all three lived during this period played a central role in their work, they transferred their Ashcan School aesthetic to more intimate scenes. Without any theoretical conceits or needs to be aligned with either European art or American movements, these men found inspiration in their surrounding environment. In many ways, they sought to embody the American experience by portraying everyday life.

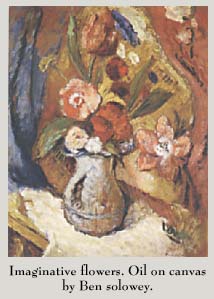

There were artists of this period who consciously looked to the past for the subject matter of their work. Artists such as Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood looked to simpler times, a world that was rapidly disappearing as the century progressed. Ben Solowey did not grieve over a loss of a way life in the past. His was a usable past. For Ben, the past had not been rendered obsolete; his genius was to transform it into timeless themes in his work and into a home and studio that suited his needs. Ben and Rae did not have a nostalgia for simplicity and self-sufficiency, they lived it. In this way they were part of America who found a renewed reverence for rural life

as a source of strength. Ben surrounded himself with simple objects that were either two hundred years old or made to look that way because he believed simplicity was the hallmark of beauty.

surrounded himself with simple objects that were either two hundred years old or made to look that way because he believed simplicity was the hallmark of beauty.

Ben was not part of the WPA in the Thirties and characteristically he made his own way. He was an early content provider in the reigning media of his day: newspapers. Ben's Theater Portraits were seen by millions in The New York Times and Herald Tribune, yet they only took a few hours of his week. That income allowed him to devote the rest of his time to easel painting

which was exhibited at institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Chicago Institute of Art and galleries around the city. He was a maverick who painted what he wanted. Even his move to Bucks County can be seen as a move of independence. Here he found a world where he could have the time and space to command his own destiny.

maverick who painted what he wanted. Even his move to Bucks County can be seen as a move of independence. Here he found a world where he could have the time and space to command his own destiny.

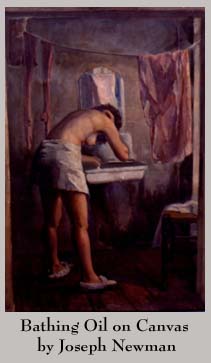

Ben transcribed his intimate impressions of the world onto canvas, with the help of one primary model, his wife Rae. These artists all had an individual model that defined their work. Joseph Newman regularly captured his family at home or in his studio in Brooklyn. Newman's daily life as seen through his work describes a certain melancholy. He looked to the order and simplicity of the Masters for painting his vernacular scenes. Newman's art emphasizes a formal quality, one highlighted by his personal response, natural for an artist who finds his subject matter so close to home. His women are patient and stable; icons of domesticity who seem unaware of the artist in their midst. Yet they are also alone, pensive, almost brooding, in varying states of dress. They exude a vulnerability, passively waiting for something or someone.

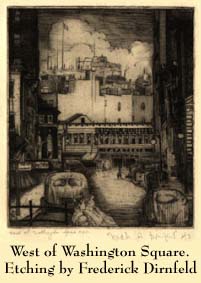

Frederick Dirnfeld's primary muse was New York City. The activity of a teeming metropolis is transcribed in scratches and burns on a copper plate and transmuted into images that trigger latent or forgotten experiences and emotions. Dirnfeld had a quintessentially American view of the city. More interested in the public than the private experience, Dirnfeld's figure studies have a warmth to them, but it his scenes of Manhattan that are his best work. They glow with an insider's perspective of the city and its unique treasures. There is the frozen moment of life west of Washington Square (seen above) and another that shows a figure by a window reading

. Dirnfeld is an observer not a critic and he allows us to see his environment through his eyes.

and another that shows a figure by a window reading

. Dirnfeld is an observer not a critic and he allows us to see his environment through his eyes.

These men did not subscribe to any manifesto of beliefs or reasons to paint. All three painted and printed as a strongly felt need. And did so regardless if they were in fashion. While Ben's work has always found an audience, the works of Frederick Dirnfeld and Joseph Newman deserved to be rediscovered. Like Ben, their worlds inspired them, and their work captured a world outside of time. Yet this work could only have been done in what Rae Solowey used to call the "halcyon days" of the Twenties, Thirties & Forties.

Studio of Ben Solowey Home Page

© 2002 The Ben Solowey Collection. All Rights Reserved.