|

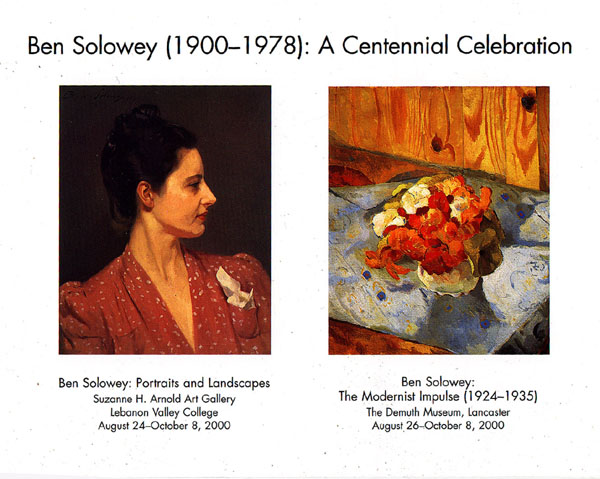

Portraits and Landscapes

Suzanne H. Arnold Art Galllery

Lebanon Valley College

August 24 - October 8, 2000

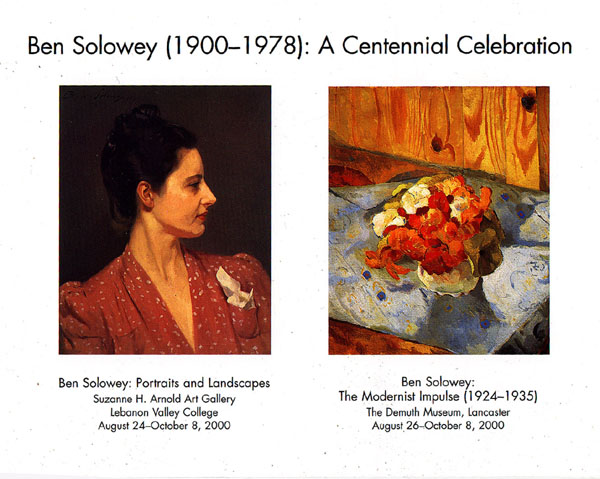

The Modernist Impulse

The Demuth Museum, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

August 26 - October 8, 2000

Essay by Dr. Leo Mazow

|

The critic Roland Barthes once commented: "In front of the lens I am at the same time: the one I think I am, the one I want others to think I am, the one the photographer thinks I am, and the one he makes use of to exhibit his art." Although he limits his observations to literature and photography, his comments are useful in interpreting the diverse creations of the American artist, Ben Solowey (1900-1978). In a career spanning almost seven decades, Solowey, like Barthes' subject, assumed many identities concurrently, working as a modernist artist, portrait painter, sculptor, printmaker, and newspaper illustrator. Yet the Poland-born artist who emigrated to the United States in 1914 and who settled permanently in Bedminster, Bucks County, Pennsylvania in 1942, madesignificant forays into other fields and disciplines as well, including furniture design and cabinetmaking

Solowey channeled his efforts, however, into his practice as a visual artist, obtaining training at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (and elsewhere), which he augmented with an important trip to Europe in 1924. Yet, precisely because he worked in diverse media and genres, it is difficult to assign him a place within the conventional ism's in the history of art. The present pair of exhibitions celebrates the artist's profoundly divergent styles, highlighting his achievements in au courant modernism and in more traditional, academic portraiture and landscape painting. Somewhat paradoxically, it is impossible to separate Solowey-the-modernist from Solowey-the-traditionalist. Many of the works in Ben Solowey: The Modernist Impulse underscore the artist's conviction that the avant garde must reckon with the conventional. The paintings in Ben Solowey: Portraits and Landscapes, in turn, demonstrate the artist's ability to synthesize a remarkable range of styles--modern and historical--and arrive at a sophisticated, individualized aesthetic.

The Modernist Impulse

Living in New York City from 1930 through 1942, Solowey was uniquely poised to experience firsthand the spirit of modernism. An avid museum visitor, Solowey and his new bride walked the city's many "museum miles," as his wife would later recall. Moreover, their neighbors and good friends in New York included several painters in the forefront of modernism, including the abstract expressionist Arshile Gorky (1904-1948), the surrealist Roberto Matta (b. 1911), the social realist Diego Rivera (1886-1957), and his painter-wife Frida Kahlo (1907-1954). That the modern impulse literally surrounded Solowey is hardly an exaggeration.

Several works in this exhibition suggest that Solowey assimilated, but ultimately personalized, the lessons offered by contemporary modernist painting. His watercolor, New England Landscape (1931), for example, contains loosely applied forms, suggesting the ephemeral compositions of the American painter John Marin (1870-1953). Yet, where the latter artist imbues his abstract surfaces with drama and movement, Solowey distinguishes clearly between fore-, middle-, and background, and stabilizes the picture with the tree at right, thereby making order out of nature's chaos. In his figural works, the artist also pays tribute to--but modifies--the enormously popular styles of such artists as Paul Cezanne (1839-1906) and Henri Matisse (1869-1954). The simplified coloration and stylized, protracted bodies in The Three Graces (1932) evoke Matisse's "Dance" and "Music" paintings from c. 1908-1913. Similarly, in the Bathers (1930), the artist elongates the human form and uses a color scheme and compositional layout strongly reminiscent of Cezanne's "Bathers" series.

Similarly, Solowey's still lifes suggest an understanding of, and elaboration upon, Cezanne's reduction of the picture plane to its underlying geometries. And it is perhaps in his still-life paintings that Solowey most strongly matches the experimental tendencies of late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century modernism. Shortly before and during his New York years, the artist produced several remarkable works in the genre. In Pansies (c. 1925-1928) and Broken Pitcher, Mountainview Farm, New Hampshire (1929), Solowey explores the fragmentation and dissolution of form, capturing the flux and impermanence of even the most solid objects. The strongly tilted tabletops appear to be on the verge of spilling out of their fictive two-dimensional realm into the viewer's actual space. This effect is especially evident in Nasturtiums (c. 1935), in which the artist silhouettes the floral arrangement against the cloth, producing a tenuous figure-ground relationship. Yet, where Cezanne exploited the precariousness of table-bound objects, Solowey produced a measure of stasis. Indeed, the upper right quadrant in Nasturtiums is a compositionally stabilizing foil to the white and blue shadows on the tablecloth. The orange and brown tones of the wood are repeated in the table and the flowers themselves, also contributing to the picture's unity.

Solowey was apparently captivated when he saw Cezanne's work on his 1924 trip to Europe. Moreover, Solowey owned several Cezanne monographs--including Roger Fry's Cezanne: A Study of His Development (1927) and Ambroise Vollard's Paul Cezanne: His Life and Art (1926). It is more than likely that Solowey, like many artists of his generation, was inspired by his radical approach to the picture plane. But the extent to which the highly individualistic Solowey appropriated Cezanne--or any artist--is debatable. The example of Nasturtiums suggests that Solowey, in effect, borrowed selectively from Cezanne. Scholars have recently suggested that although Solowey admired modern painting from post-impressionism through cubism, he was not heavily swayed its enormous popularity. The artist certainly had disdain for modern painters with shoddy draftsmanship. Yet he praised Matisse and Picasso precisely because their abstraction evolved from an understanding of, and training in, traditional drawing. For Solowey, modernist and more conventional painting were not mutually exclusive categories; rather, they were closely related.

Portraits and Landscapes

Solowey found in modern European painting less a guiding force than a set of aesthetic principles complementing his own artistic goals. Several markedly unmodernist works in this exhibition suggest an experimental spirit and reductionist propensity one normally associates with modernism. Solowey's pastel work, Rae (c. 1937), for example, captures the figure's psychological intensity through an economy of artistic means--a series of bold lines and broad planes of color. In a later discussion he echoed a similar modernist ethos as he advocated the elimination of particulars locate the subject's essence. Sounding more like a cubist or an expressionist, he explained: "I lean to a simplicity which has room only for those details which can effectively become part of the whole."

Solowey also adapts modernism to his own vision in works like Landscape with Red Barn (1940) and Farm House Group (1940). In the latter painting, the artist positions the houses amid the foliage of the middle ground, relegating the architecture to an array of subtle geometric planes, suggesting an affinity with contemporary "precisionist" artists such as Charles Demuth (1883-1935) and his fellow Bucks County resident Charles Sheeler (1883-1965). Yet in its dramatic horizontal format, its ambitious coloration and spacemaking, and its reconciliation of natural and artificial elements, Farm House Group attests to the artist's subjective interpretation of the rural Pennsylvania countryside. This and other seemingly "academic" works in this exhibition are significant because their conventional subject matter only partially veils the wealth of painterly skills and understanding of artistic precedents that Solowey had at his command.

While entrenched in modernist New York, Solowey produced over 900 drawings of celebrities of stage and screen which were reproduced in the New York Herald Tribune, New York Times, and New York Post. Throughout this period he produced likenesses of many of the most renowned actors and performers of the day, including Ethel Barrymore, Noel Coward, Lillian Gish, Helen Hayes, Katharine Hepburn, Laurence Olivier, Claude Rains, and Spencer Tracy. Joining naturalistic detail with theatrical gestures and poses, Solowey emerged as a leading portraitist-illustrator during these years, and the "Solowey theater portrait" came to be esteemed by actors and audience alike. Ironically, because he often produced the images in a matter of minutes, usually on the set during an actor's break, many of these portraits appear rapidly executed, possessing a spontaneity and abstraction akin to the more modernist works discussed above.

Solowey's most important sitter and model, however, was his wife Rae. Solowey first painted Rae in 1930, the year the two married, and she would be his primary model for the rest of his life. Although many of these images harken to classic renditions of the female subject, they suggest in particular the highly charged mental states and pensive dispositions found in the late portraiture of Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), whose works and reputation Solowey surely encountered during his student days at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (where Eakins taught until his forced resignation in 1886). Possessing what one might call archetypal facial features, Rae appears in several works in the present exhibition, assuming a wide variety of poses with the grace and bearing of a professional artist's model. The 1939 oil-on-canvas image of Rae, reproduced here, differs from other portraits in its turning profile pose and self-conscious affectation. Yet psychologically, it may be considered a study in opposites. Turning away, she denies her gaze to the beholder in a manner suggesting John Singer Sargent's (1856-1925) painting, Madame X (1884; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Yet the sensitive lighting and modeling of the face and the cropping of the figure at the bottom of the picture plane yield a warm accessibility in spite of her turning head.

Notwithstanding the image reproduced here, several paintings of Rae highlight her hands, which Solowey depicts almost as expressively as her face. Similarly, in his own Self Portrait in Studio (1958), his left hand may be the most well-lit part of the picture. The artist envisioned the practice of painting as a convergence of mental and manual faculties, and Solowey, appropriately, pictures himself laboring with his head and his hands. The emphasis upon hands suggests a concern with sound handcraftsmanship, which was central to the artist's enterprise and was also a catch phrase for the turn-of-the-century Arts and Crafts Movement. For his part, Solowey rebuilt and refurbished the eighteenth-century structure in Bedminster that would become his family home and studio. He was such a skilled carpenter and woodworker that it is misleading to think of his carpentry as simply an avocation. It is therefore not surprising to find in Solowey's studio (which remains in near-original condition), just above his drafting table, his used copy of Every-Day Art (1882), by Lewis Foreman Day, a leading designer in the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Solowey's copy of the text contains the following passage, underlined in pen: "It is beyond dispute that the influence of our everyday surroundings must affect us, and possibly influence us much more powerfully than we are accustomed to suspect." It is unclear whether Solowey or the book's previous owner underscored these lines, but the passage matches Solowey's philosophy and offers an interpretation of the world he and Rae built for themselves in Bedminster. Solowey's artistic statement late in his life summarizes this credo: "It seems to me that there is usually an affinity between the things people think and do, and the things they have surrounding them. It must be hoped that one accustomed by inclination and training to distinguish between good and bad in line and color is influenced positively."

Studio of Ben Solowey Home Page

© 2000 The Ben Solowey Collection and Leo Mazow. All Rights Reserved.