Twilight: The Late Work of Ben Solowey

September 24 - October 29, 2000

Twilight: The Late Work of Ben Solowey

September 24 - October 29, 2000

TWILIGHT: The Late Work of Ben Solowey was the first exhibition to focus on the years 1966 to 1978, the final period of Ben's nearly seven decade career. Despite being bracketed by disease — he suffered a heart attack in 1966 — and his death in 1978, it was a rewarding time for Ben in terms of his work and its recognition.

In April 1966 Ben’s lifetime of smoking caused a serious coronary attack and for the first time in his life he was unable to do many of the tasks he enjoyed. Ben was a tireless worker; painting, drawing, sculpting, frame-making, cabinetmaking, and gardening filled most of his waking hours and one feels he enjoyed every minute of it. Here was a lucky man who was doing exactly what he wanted.

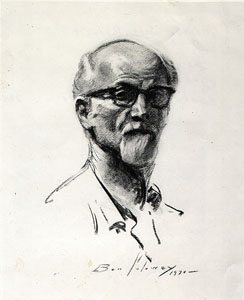

"He was a perfectionist, both in his work and in the details of daily living," artist Albert Gold wrote in a 1979 remembrance of Ben. "He was devoid of self-doubt. He knew he was very good. His justifiable ego confronts us from his many self-portraits in every medium. He was unusual in that he worked equally well in Oil, Watercolor, graphic media and Sculpture."

Yet after his attack, a sense of mortality and introspection hovered around the work. The ambitious still life, Dried Flowers and Fruit, painted in the months after his illness, presented an autumnal grouping of dried flowers surrounded by chaotically draped cloths. The fruit in the center has an uneasy sheen, perhaps because the fruit was not real. This unique work can be read as a meditation on life and death, for despite its air of melancholia, its composition is rich and varied, and shows the artist at the height of his powers.

His landscapes from this period also give an air of introspection seen only rarely in earlier works. In particular, his winter landscapes, most drawn in black and white or in pastels, show his surroundings covered in snow. His economical use of line and color, allow the white of paper to project copious amounts of snow. His lifetime of observation permits him to include only what is necessary to convey the cold and the quiet of his scenes.

1966 was also the year that Ben’s Theater Portraits were the subject of a record-breaking exhibition at the newly built Lincoln Center in New York. This display of over 100 of his charcoal portraits was originally scheduled to run six weeks. Because of the show’s popularity with visitors, its run was extended to six months.

Of course he continued to paint draw and sculpt images of Rae. The portraits of Rae from these last dozen years are suffused with a mature love. There is no doubt that Ben loved Rae from the moment he saw her, but in his final years there is palpable sense of understanding and appreciation. She continued to be his favorite model, as he seemed fascinated with her moods and gestures.

In 1973 and 1974, Ben drew composites of both Rae and himself in various attitudes that seem more like diaries than anything else. The composites, with their compact portraits right next to each other, reveal a range of emotions. As Albert Gold wrote, his self-portraits present a "justifiable ego," but those same works from this period also show a witty side as well. In one case, the plaster sculpture Laughing Mask, he shows himself not as the serious artist of almost all his other works, but a man tickled by life.

Many of his still lifes from this period also revel in the beautiful abundance of his garden. Many of Ben’s floral works from 1942 were culled from the garden right outside his studio. He would often ask Rae to gather and arrange a composition. These works, filled with a summer light and color, are almost raucous celebrations of nature. He often painted these still lifes as if they were portraits, focusing on the blossoms in the foreground, while a draped cloth serves as the background.

His restless spirit was never contained. Even at an advanced age, he continually tried new techniques and media. Perhaps his most sustained experiment with a new medium was the introduction of etching. In 1974, on a visit to the great animal illustrator Paul Bransom’s home in the Adirondacks, Bransom gifted his friend an antique etching press. Ben dismantled the press, tagged each piece and drove it back to Bucks County. There he reassembled it, and Rae marveled that "there was not one screw left over."

His approach to etching was much like anything else. He subscribed to no formula in his attack. Without any formal training, he worked the plates, and each time he pulled a print he marked its development at the bottom of the page. Sometimes he might use a plate in the same state but try different papers in varying textures and/or colors. In this way, each print pulled was a unique work. He never produced a number edition, and to make matter confusing to historians, he sometimes inscribed different names on the same images. For Ben the joy was in the creation of the work.

In the end, he did not care about posterity. The reason the Studio and its collection exist today was not because Ben wanted others to marvel at his accomplishments, but rather because Rae wanted people to experience what she had been lucky to enjoy for most of her life.

Top: Dried Flowers and Fruit

Oil on canvas, 36 x 48", 1966

Bottom: Self Portrait

Charcoal, 24 x 18", 1970

Studio of Ben Solowey Home Page

© 2002 The Ben Solowey Collection. All Rights Reserved.