Philip Barry’s play, The Philadelphia Story debuted on Broadway on March 28, 1939. Barry had written the romantic comedy specifically for Katharine Hepburn, and she was so eager to rid of herself of the stench of “box office poison” after her last few films had failed, that she became an unbilled producer of the play with the Theatre Guild, and took no pay but got a portion of the show’s profits. And it was hit, running for 417 performances in a little more than a year. It would have undoubtedly won several Tonys, but they had not yet been created.

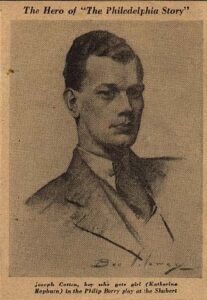

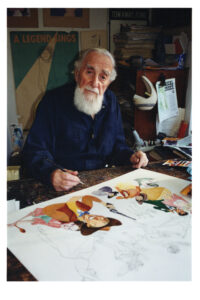

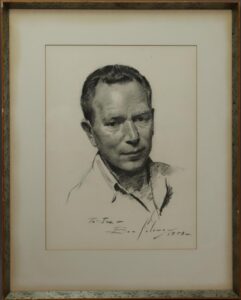

Ben Solowey drew five members of the cast of the Broadway production. The first was Hepburn’s co-star Joseph Cotten who originated the role of C.K. Dexter Haven, played in the film by Cary Grant. Cotten loved his portrait so much he purchased it for $50, which he paid in $10 installments over several months.

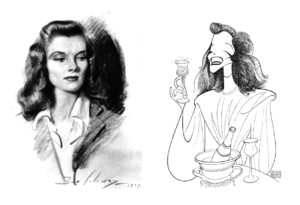

The Herald Tribune asked Ben for a portrait of Hepburn and her other co-star, Van Heflin, who played the role that won Jimmy Stewart his only Oscar. “I was told, ‘She’s rough; she’ll give you a hell of a time,’” remembered Ben to a Philadelphia Inquirer reporter in 1977. “I went backstage after seeing her in The Philadelphia Story. ‘All right,’ she said, ‘let’s go,’ and about midnight I went with her and one of her co-stars, Van Heflin, to her apartment. I had he sit on her kitchen table for a couple of hours. She offered me a drink and a banana. And she was so pleased with the drawings she bought it.” Hepburn paid for her drawing with one check, less than three weeks after it appeared in the paper, and so did Van Heflin.

Despite showing regularly with painters like Picasso, Matisse, de Kooning and Hopper, painting great canvases, restoring his 34-acre farm, the thing that people remembered about Ben was his interaction with Hepburn. When asked about her, he would simply reply that she had a good head, which caused people to send him clippings of her picture whenever it ran in the paper. Rae would eventually tack some of those clippings, along with one of Ben’s drawing on his studio door.

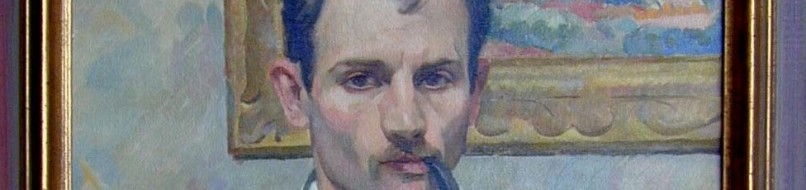

Al Hirschfeld did not draw the original production while it was on Broadway, but he did contribute thumbnail portraits of New York theater critics whose complimentary blurbs about the show were on the back of the souvenir program. Although he would draw Hepburn in several stage productions and many of her films, he did not draw her in the role again until the 1973 book, The Lively Years by Brooks Atkinson, which he illustrated.

In 1990, he was commissioned to draw her again in this iconic role. He liked it so much he asked for a full-size reproduction to be made that he inscribed and sent over to her. It turned out that Hirschfeld and Hepburn had a mutual admiration society for decades, and she collected a number of his drawings of herself for her home. This drawing proved to be so popular that it was published as a hand signed, limited edition lithograph, one of which will be in the Hirschfeld exhibition. You can see both “Kates” during the run of this exhibition.

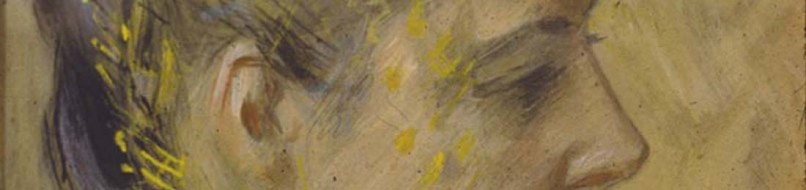

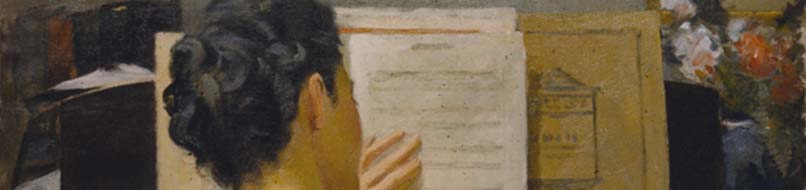

![[Portrait of Dark Haired Young Woman]. Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 in. c. 1924-28](https://www.solowey.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Solowey_Black-Haired-Woman-252x300.jpg)