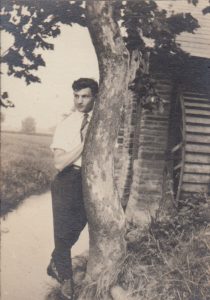

From the Solowey Studio Archive

Jun 5th, 2018 by David Leopold

From the Solowey Studio Archive

Jun 5th, 2018 by David Leopold

Special Event: June 16th Sherlock Jr.

May 18th, 2018 by David Leopold

Sherlock Jr.

Starring Buster Keaton

with live musical accompaniment by theater organist Brett Miller

June 16, 2018

Doors open 7:30 pm; Film at 8:00 pm

Did you ever wish to know what it was like in the 1920s? Time travel may still be far off, but for one night we hope to transport you back to that golden age when movies were silent and musicians made the noise.

In conjunction with our new exhibition, “Portrait of the Artist as Young Man: The Early Work of Ben Solowey,” we are bringing back the “boy wonder” of the theater organ, Brett Miller, to accompany Buster Keaton’s silent classic, Sherlock Jr. This 1924 comedy is one of Keaton’s best-loved films, equally embraced by long-time aficionados as well as newcomers to silent comedy. In fact, modern audiences easily take to the fast pace and complex film-within-a-film motif. Set mostly in a dream, Pauline Kael called it “a piece of native American surrealism.”

Buster is the projectionist and janitor of a small-town movie theatre. The projectionist’s real ambition is to become a master detective. He would also like to win the heart of a local girl, though he is short of funds and must also compete with a conniving rival suitor, who sets up Buster to take the fall for his crime. When Buster returns to the projection room, he falls asleep and it is during his “dream” that real hijinks ensue.

Seating is limited to 40, and if past screenings are any indication, tickets will go fast. This is a benefit for the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, and tickets are $20. To reserve a ticket contact us with your credit card and we will save your seats. You can call 215-795-0228 or email us at RSVP@solowey.com.

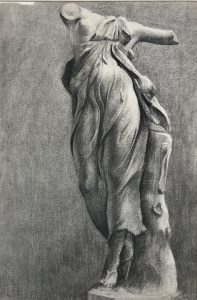

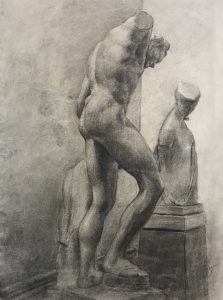

Cast in Charcoal

May 2nd, 2018 by David Leopold

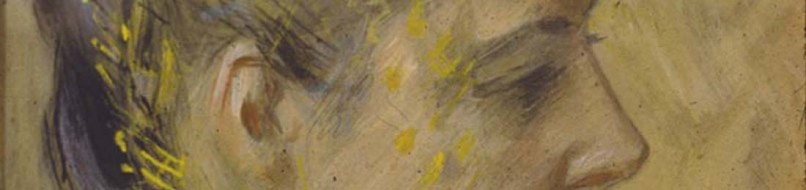

The Earliest Solowey Drawings from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

The earliest works of Ben Solowey that remain today are those from his time at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). Ben enrolled in classes in 1919, beginning his formal study of art that would lead to his lifelong career/passion. The Academy was founded in 1805 and is the first and oldest art museum and school in the United States, and at the time that Ben attended it offered a classical approach to making art.

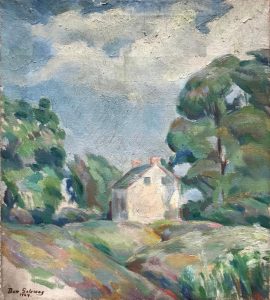

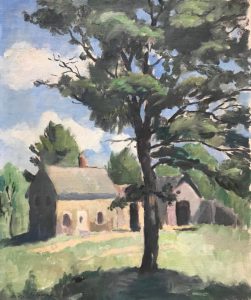

Terra Incognita

May 2nd, 2018 by David Leopold

Early Solowey Landscapes of Chester Springs

See for yourself on June 9th, when we open our news show Portrait of the Artist As A Young Man: The Early Work of Ben Solowey from 1 to 5 pm. We will be also opening the Solowey home and fill it with home made refreshments as usual.

-David Leopold

2017

Jan 13th, 2017 by David Leopold

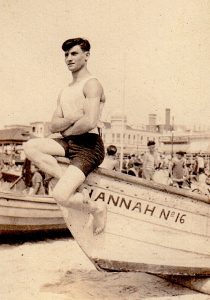

2017 marks two special anniversaries for The Studio of Ben Solowey. 75 years ago, Ben and Rae Solowey moved permanently to Bucks County. 25 years ago, we began to present regular interpretive exhibitions at the Solowey studio of Ben’s work, his contemporaries, and occasionally a contemporary artist. Our plan is to celebrate both anniversaries this year with exhibitions in the summer and fall, along with special events and programming starting this spring.

Ben and Rae had bought the 34-acre farm on which the studio sits in 1936. Armed with real estate sections from the New York Times and Herald Tribune, they left their Fifth Avenue home and studio and came out to Pipersville, Pennsylvania in upper Bucks County where a local farmer, Reed Nash, who moonlighted as a real estate agent, took them to thirteen different properties before they stopped on the main road outside of the village of Bedminster, at the end of a quarter mile driveway to a small farm. It was April, and it had rained, and the horse and buggy tracks that served as the driveway were not sufficient to drive a car on, so the Soloweys got up and walked up the path. According to Rae, by the time Ben got to the barn, he had decided that this property would be the last they would visit that day. He had found a new home.

What Ben saw in it that day is hard to say. It was pretty run down, with Rae comparing it to the poor tenant farms of the novel Tobacco Road. It had no running water or electricity and it was miles from anywhere. It may have been precisely those reasons that attracted Ben, 41, for he had a vision of what it could become and looked forward to the effort to make it a reality.

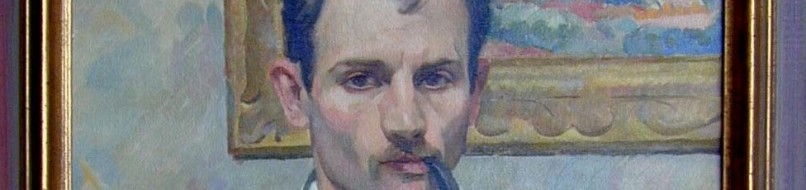

For the next six years the Soloweys went back and forth to New York, increasingly spending more time at the farm. That may have continued their trips, but with gas rationing at the start of World War II, they had to decide whether they were going to be city or country. It seems that everyone, including Rae thought they would remain in New York, where Ben had established himself a renowned painter and was acclaimed for his “Theater Portraits†that appeared regularly in the Sunday editions of the New York Times and the Herald Tribune. They had a beautiful home and studio on Fifth Avenue and 12th Street, and many friends and neighbors such as Arshile Gorky, Diego Rivera, Freda Kahlo, Ford Maddox Ford, along with a steady stream of theater people who regularly came to Ben’s studio to be drawn. Nevertheless, Ben decided to go to Bucks County, and the Soloweys moved in November 1942. Ben would remain on the farm until his death in 1978, and Rae would live here until her passing in 1990.

It was Rae’s wish that Ben’s studio be open for future generations to enjoy. She was not clear on exactly how that was to happen, as she did not want to dictate the course when she not be here to help. Although there was support from family, friends and collectors, almost all were sure that no one would come to a remote location to see the studio and the work in it, and if they came, they would not make the trip again. In 1992, we presented our first exhibition, “A Place for All Seasons.†Ben’s name and art, and the fact that this was the only intact artist studio from the Golden Age of Bucks County, attracted visitors. Exhibitions and positive reviews followed, and soon we decided to limit the number of people on our mailing list for the simple reason that we did not want to alter either the property or the community with larger crowds.

Early on, the Studio was described as “Bucks County Best Kept Secret†and that is still true today. Although the studio has been fortunate to receive press both in the region and in major publications around the country, it does no advertising. We have no real gift shop or tea room, and for years people had only a mowed field to park their cars, yet they still came, often bringing friends with them. Articles on the Studio also brought out new visitors, and the cycle continues today.

Early on, the Studio was described as “Bucks County Best Kept Secret†and that is still true today. Although the studio has been fortunate to receive press both in the region and in major publications around the country, it does no advertising. We have no real gift shop or tea room, and for years people had only a mowed field to park their cars, yet they still came, often bringing friends with them. Articles on the Studio also brought out new visitors, and the cycle continues today.

Over these last 25 years we have presented more than 40 exhibitions on different aspects of Ben’s career. Some of these shows have traveled to museums and galleries, and we regularly loan Solowey works to other exhibitions, both local and national. We feel that we not only have fulfilled Rae’s wish for the Studio, but also fill a need in the region as both a historic and arts venue.

It is remarkable that the studio and the farm have changed so little in the intervening years, as has the surrounding environment. The property is still farmed by the same fellow who farmed it in Ben’s time, although he is a grandfather now. The studio has remained intact not because we left everything in the same place, but as anyone who has visited knows, it is because we regularly move pieces around, much like Ben did when he was working. While one does not have to go far to see “progress,†when one stands at the Studio they are seeing virtually the same landscape Ben saw that April afternoon in 1936, save for the trees, many of which Ben planted.

Next month, we will announce our two new exhibitions this year and reveal some of our special programming to go with them. We will send monthly updates through our email newsletter. If you want to receive an invitation in the US mail, write to info@solowey.com with your address.

This is going to be a special year for the Studio of Ben Solowey and we hope to see you out here. As Rae was so fond of saying—

We’ll see you when we do….

On the Other Side of the Easel

Jan 12th, 2017 by David Leopold

For more than 25 years I have both literally and figuratively looked over the artist’s shoulder as he/she works at an easel. That’s what curators do. We want to see not only what the artist has created, but when possible, how they did it, what was their motivation, and what was the context. Sometimes it feels like putting together the pieces of a puzzle, with the best result being a complete picture with every piece in its place. This rarely happens because…a wide range of reasons. Most artists rarely keep detailed diaries of why and how they are working and memories are faulty or circumspect. An artist can have reasons why a work was created and ten years later look at the same work and see a different set of reasons. 25 years or more, the artist may have different reasons then the first two proffered. It isn’t that the artist is lying, it is simply human nature to see things differently as we get distance from them. Curators try to provide the history and context of a chosen work for an exhibition or publication from extant evidence, but rarely are in the studio while the artist works to observe and ask questions.

During the run of our last exhibition, Leaving a Mark: Second Annual Works on Paper Exhibition, we invited Paul DuSold to return to the Solowey Studio to present one of his celebrated portrait demonstrations. Visitors may remember that in 2010, during the run of a joint exhibition of Solowey and DuSold paintings here at the Solowey Studio (one of the two times we have showed a contemporary artist’s work here), Paul made history by painting the first work in the studio since Ben Solowey’s death in 1978.

Paul is one of the few accomplished portrait painters who not only can capture the personality of his sitter, bu t also speak intelligently to an audience while doing it. In his first demonstration, he worked in oils before a rapt audience. This time we asked if he would draw rather than paint in honor of the exhibition. He agreed, a date was set, and a model was engaged. As the day approached, our model was unable to make it. I called someone else, but they were unable to come, so as the morning broke, I realized that since my wife and son were unavailable or unwilling, I would take the chair on Ben’s model stand and sit for Paul.

t also speak intelligently to an audience while doing it. In his first demonstration, he worked in oils before a rapt audience. This time we asked if he would draw rather than paint in honor of the exhibition. He agreed, a date was set, and a model was engaged. As the day approached, our model was unable to make it. I called someone else, but they were unable to come, so as the morning broke, I realized that since my wife and son were unavailable or unwilling, I would take the chair on Ben’s model stand and sit for Paul.

I was to have done that once before, in the fall of 1978, when my twin brother John and I were to have sat for a portrait by Ben himself. In the family, when one approached the age of 13, someone—frequently Rae’s sister Rick—often commissioned Ben to draw a portrait. My late sister Ann had sat for a lovely pastel portrait at the age of only eight, and my older brother Matthew had sat for a charcoal drawing at 13. Rae would later tell me that Ben was looking forward to drawing my portrait and John’s because he could not tell us apart, but he knew that once we sitting in front of him our distinct personalities would make it clear who was who. Unfortunately, Ben died three months before the portrait was to have been drawn. At the time, it was of little consequence, but over the years and my deepening involvement with all things Solowey, I regretted that we were denied the experience of sitting for Ben.

Special Event: October 15th

Sep 2nd, 2016 by David Leopold

On Saturday October 15th, award-winning artist Paul DuSold will give a portrait demonstration in the Main Studio at 2:30 pm. Visitors may remember that six years ago, during the run of a joint exhibition of Solowey and DuSold work here at the Solowey Studio, DuSold made history by painting the first work in the studio since Ben Solowey’s death in 1978.

On Saturday October 15th, award-winning artist Paul DuSold will give a portrait demonstration in the Main Studio at 2:30 pm. Visitors may remember that six years ago, during the run of a joint exhibition of Solowey and DuSold work here at the Solowey Studio, DuSold made history by painting the first work in the studio since Ben Solowey’s death in 1978.

Like Ben, DuSold is one of the few accomplished portrait painters who not only can capture the personality of his sitter, but also speak intelligently to an audience while doing it. We are thrilled to have Paul return to create a new portrait in Ben’s remarkable studio. He will be drawing this time instead of painting, in honor of our works on paper exhibition. You won’t want to miss this opportunity to see DuSold in action.

The day after this demonstration, DuSold’s work will be featured in a new exhibition, The Nude, Mirror of Desire opening at the Wayne Art Center through November 19, 2016. The show also includes the work of Scott Noel, Ben Kamihira and Margaret MCanne. To learn more about DuSold and his art, visit pauldusold.com.

Special Event: October 22nd

Sep 1st, 2016 by David Leopold

Please join us for our first film event on October 22nd at 7 pm. This special showing of the classic silent film, Nosferatu in the Halloween season is sure to memorable, as it is not only considered a film masterpiece, but it will have live musical accompaniment by the “boy wonder†of the theater organ, Brett Miller.

Please join us for our first film event on October 22nd at 7 pm. This special showing of the classic silent film, Nosferatu in the Halloween season is sure to memorable, as it is not only considered a film masterpiece, but it will have live musical accompaniment by the “boy wonder†of the theater organ, Brett Miller.

Brett is an organ prodigy who has studied with the top organists in the country. Bucks County’s County Theater hires him to play at all four of their theaters, and he is a staff organist at Loews Jersey City, one of the classic movie palaces from the 1920s. Analyzing the film, Brett has composed a score that is firmly rooted in the classic silent film tradition.

Nosferatu, according to film critic Roger Ebert, “is the story of Dracula before it was buried alive in clichés, jokes, TV skits, cartoons and more than thirty other films. The film is in awe of its material. It seems to really believe in vampires… It doesn’t scare us, but it haunts us.†Directed by the legendary F.W. Murnau, it draws on the great visual tradition of the early silent, when images were more important than words. If you have never seen a silent film, or never seen one with live music, this is a must. If you have, you won’t want to miss this special presentation.

Tickets are $10 as the event will be a benefit for the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. Seating is limited and tickets are already going fast. to reserve yours, contact the Studio by email at RSVP@solowey.com or by phone at 215-795-0228.

After Ingres

May 13th, 2016 by David Leopold

To highlight works in the exhibition, Homage: Ben solowey’s Art iNspired by His Influences, we are providing articles on the artists he admired and the works they inspired:

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780 – 1867) was on a quest to capture the ideal beauty. A student of Jacques-Louis David, then Europe’s greatest artist, Ingres learned the Neoclassical style but soon emphasized the contours of his figures, in a way, becoming one of the first Modern painters. Though he was dedicated to the academic panting of the classical era in his early life, he would eventually become experimental in his art, breaking many of the boundaries set by the classical painters.

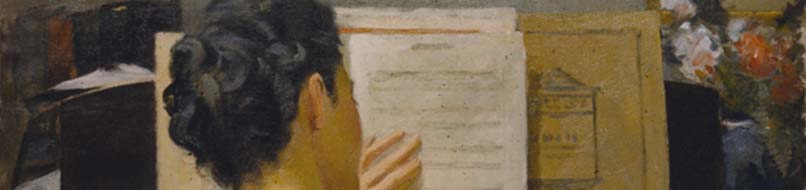

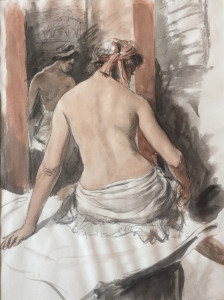

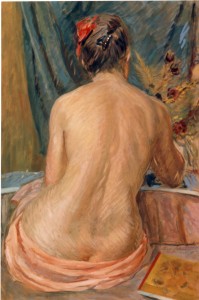

Like Ben, Ingres felt that drawing was the foundation of art, and his paintings and drawings reveal his detailed approach to draughtsmanship. Ben Solowey collected reproductions of both his drawings and of his most famous paintings, “La Grande Odalisque,†one of the first pure nudes (without any historical justification), which Ben alluded to in a number of works throughout his career, and “The Valpincon Bather.â€

“The Valpincon Bather†is one of Ingres’ most renowned works. The nude, seen from the back, has many anatomical distortions that would become synonymous with Ingres. This work is considered to be his first great work of the nude. One critic remarked “Rembrandt himself would have coveted the amber colour of this pale torso.” The painting would inspire a number of Solowey paintings and drawings, and like Ingres himself, he would return to the figure throughout his career. He kept a reproduction of the work in his studio and in his oil, “Still Life Materials,” now in the collection of the James A. Michener Art Museum, which depicts elements of still life paintings, he included the reproduction – a direct acknowledgement of the inspiration, virtually the only time he made such a direct link.

In an undated work on paper, Ben brings a soft treatment of the body to his own version of the Valpincon Bather. Here, Rae models for this modern adaptation in his New York studio. The pose is not identical, but the view of the bather from the back along with the pink and white turban hints to the Ingres tradition Solowey is drawing upon. He combines it with a fascination with mirrors that can be traced to the work of Manet. With the addition of the mirror, we can see the front of the nude, though the reflection is dark and less defined. While much of the background has a sketch quality to it, the skin of the nude is soft and supple, not unlike the original Ingres’ work. Ben stayed true to reality with anatomically correct proportions.

In an undated work on paper, Ben brings a soft treatment of the body to his own version of the Valpincon Bather. Here, Rae models for this modern adaptation in his New York studio. The pose is not identical, but the view of the bather from the back along with the pink and white turban hints to the Ingres tradition Solowey is drawing upon. He combines it with a fascination with mirrors that can be traced to the work of Manet. With the addition of the mirror, we can see the front of the nude, though the reflection is dark and less defined. While much of the background has a sketch quality to it, the skin of the nude is soft and supple, not unlike the original Ingres’ work. Ben stayed true to reality with anatomically correct proportions.

“Red Ribbon,†a 1956 casein, also pays tributes to Ingres’ classic work, this time painted in the distinct Solowey style with vibrant colors and Rae modeling once again.

“Red Ribbon,†a 1956 casein, also pays tributes to Ingres’ classic work, this time painted in the distinct Solowey style with vibrant colors and Rae modeling once again.

In a 1950 oil, “Pink Turban,†Ben turns his model around and gives us a portrait of Rae, as if to to reveal the identity of his bather. It was a work that must have been close to his heart and his made the canvas himself, and in our Homage exhibition, it is one of Ben’s best hand carved, gold  leaf frames.

leaf frames.

Katherine Eastman

Associate Curator