The influence of Gilbert and Sullivan can be seen and heard all around us. Musicians and lyricists alike were influenced by the duo, including songwriters and composers from Irving Berlin to Andrew Lloyd Weber. Gilbert’s lyrics set the stage for the American musical to be born, with songs directly referencing the plot and addressing both political and social issues of the day. The strong parodies of everyday life, both good and bad, did not take away from the entertaining nature of the songs. Shows could now be both informative and entertaining! Carolyn Williams of Rutgers University even brings Gilbert and Sullivan into the 21st century, comparing the duo to Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, “casting a critical eye to the day’s political and cultural obsessions.â€

In England and all across Europe, Gilbert and Sullivan operas were performed exclusively by the D’Oyly

Carte Opera Company. D’Oyly Carte started in 1875, and was comprised of a true ensemble cast. Performers were carefully groomed for their roles and no one performer was considered more important than another. While D’Oyly Carte held the copyright for all Gilbert and Sullivan operas in England and many other locations abroad, they failed to secure the rights for American performances. Thus many Gilbert and Sullivan troupes began their own repertory in America. Unlike popular American theatre were based around a bigger star or show-stopping performer, many American Gilbert and Sullivan troupes mimicked the ensemble nature of the D’Oyly Carte and strived for productions that kept the group mentality. Vera Ross and Frank Moulan were valued members of companies like this. Both had long careers bringing Gilbert and Sullivan to American audiences.

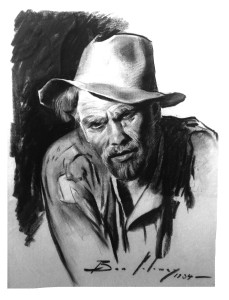

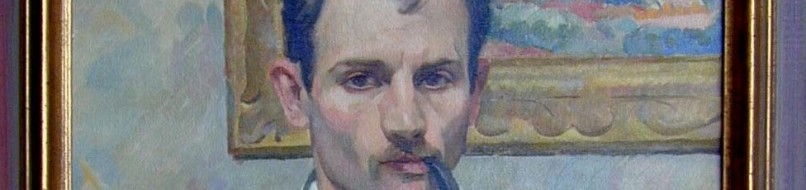

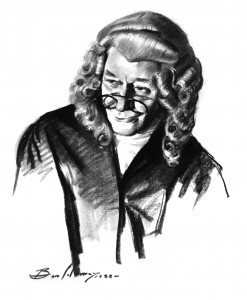

Frank Moulan was a prolific performer in the duo’s work for 37 years. His first Gilbert and Sullivan opera was H.M.S. Pinafore in 1899 with the Castle Square Opera Company. His talent as a Savoyard was immediately recognized. “He bids fair to advance to the front ranks of the comic opera comedians; he has genius,†wrote a reviewer in 1900 about his debut performance. Moulan’s career in the 20th century was almost exclusively Gilbert and Sullivan credits, totaling 31 different productions. Moulan’s 1933 portrait is from Trial by Jury, in which he played The Learned Judge.

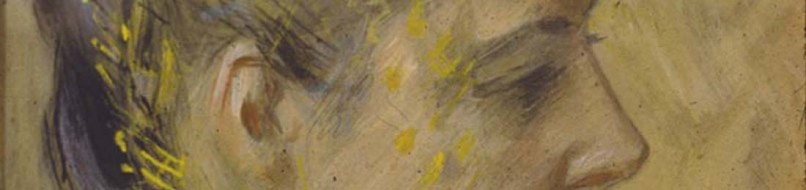

When Solowey drew Vera Ross in The Pirates of Penzance, she already had 10 years of experience with Gilbert and Sullivan operas, beginning in 1926 with a production of Iolanthe. Ross was no stranger to the pirate code. This 1935 production was her 5th time playing the role of Ruth, the contralto “piratical maid of all work,†and she would reprise the role once more in 1936.

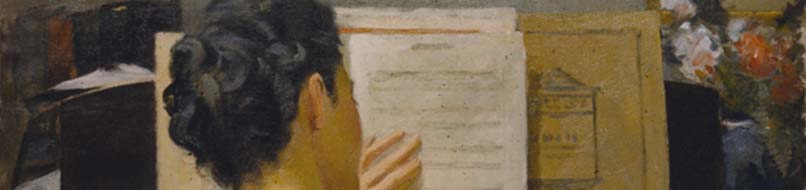

Ross and Moulan spent most of their careers with the Milton Aborn Opera Company. Aborn had been producing light and grand opera since the later 19th century and staunchly believed that audiences wanted “good music at popular prices.†Aborn, drawn by Solowey in 1931, was responsible for most of the Gilbert and Sullivan seen on Broadway in the 1920s and 1930s. After Aborn’s death that November, Ross and Moulan started working for Lodewick Vroom at the Civic Light Opera Company..

Ross’ stage career came full circle when she ended it with her fifth Broadway production of Iolanthe in 1936, costarring William Danforth, yet another Aborn Company member with an extensive list of Gilbert and Sullivan credits, and Moulan directing. Iolanthe would be the final Broadway bow for all three performers. Hollywood gave them an encore when they were cast in the film The Girl Who Said No the following year. The film follows the story of a man who revives a defunct Gilbert and Sullivan troupe to seek revenge on a girl who rejected him. While the film did not merit great reviews, the trio’s Savoyard performances were heralded. All three would soon disappear from both stage and screen. The golden age for Gilbert and Sullivan on Broadway had ended. Their operas would continue to live on, but never again be produced with such regularity as they were in this period.

The portraits of Frank Moulan and Vera Ross will be featured in the upcoming exhibition “Paper Trails†at the Studio of Ben Solowey.

Katherine Eastman

Associate Curator

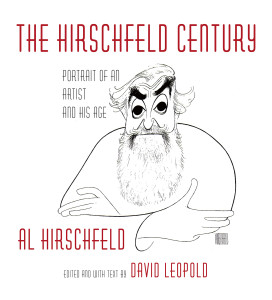

led THE HIRSCHFELD CENTURY bringing together many of his greatest drawings under one roof for the first time. It coincides with the publication of my book of the same name by Alfred A. Knopf. It is probably the best thing I have ever written and while it is only

led THE HIRSCHFELD CENTURY bringing together many of his greatest drawings under one roof for the first time. It coincides with the publication of my book of the same name by Alfred A. Knopf. It is probably the best thing I have ever written and while it is only