1993 New York in the Thirties – The Face of the American Theater

Originally published for the exhibition “New York in the Thirties”, 1993

When Rae Landis, the soon-to-be Mrs. Ben Solowey, arrived in New York on November 1, 1929 she remembered that it was “only a few days after the financial world went mad, people simply walking out of windows into eternity.”

The devastating effect of the Stock Market crash in October 1929 would soon be felt by the entire country and cast a dark shadow over the next decade. The Depression raised serious questions regarding the validity of our national life and the assumption that the future would always be bright.

It was the paradox of the 1930s that the nation’s enjoyed one of its greatest creative periods while it suffered its harshest economic times. New directions in theatre, film, opera, and dance essentially rewrote how America looked at itself and its heritage. With its new themes and new mediums, this epoch of intense innovation provided a blueprint for all the arts for years to come.

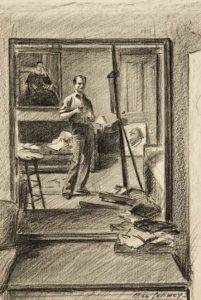

The capital of these halcyon days in the performing arts was New York, and its court artist was Ben Solowey. Through a series of nearly 900 charcoal portraits, most commissioned by The New York Times and the Herald Tribune, Ben Solowey captured this exciting era for posterity.

Like the performing arts he recorded, Ben Solowey was also a pioneer in many respects. Ben, unlike his contemporaries, insisted on working from life, often visiting the theatre during a rehearsal to delineate the performer either right on stage (frequently under a bare light bulb) while all manner of activity swirled around him or in the more private confines of an actor’s dressing room.

Because of performers’ hectic schedules, Ben sometimes had only minutes to capture the essence of his subject and the character they were portraying. Later performers took the opportunity to visit the Solowey studio on 5th Avenue in Greenwich Village where the artist could work undistracted.

Like fellow Pennsylvanians William Glackens and John Sloan, the demands of the newspapers provided Ben with an invaluable education. As noted artist and author Henry Pitz wrote, their experience was “a marvelous sharpener of quick, incisive draughtsmanship and a rough and ready spur to resilience and self reliance.”

At that time the city’s 12 daily newspapers had a stable of young artists in their employ to supply them with images for their drama pages. Many of these artists simply translated publicity photos into line drawings which were easier and cheaper to reproduce. As a classically trained artist, producing the expected line drawings would not satisfy Ben Solowey. He was the one of the first artists to introduce halftone into newspaper reproduction.

He choose charcoal because of its quick response to his hand, and preferred strong light to achieve a tonal scheme of positive values that would make an indelible mark on the page and reduce the possibility of error in reproduction. Although initially met with skepticism, his striking drawings would became the standard for a new generation of newspaper artists to emulate. To be drawn by Solowey was a sign that a performer had “arrived,” a mark of unrivaled recognition, and his portraits were eagerly awaited each week by both performers and newspaper readers.

Whether it was the permissiveness of the preceding decade that loosened the constraints of emerging playwrights or whether it was the austerity of the new decade they faced, the 1930s gave birth to some of America’s most enduring plays.

You Can’t Take it With You, Our Town, Private Lives, Awake and Sing, Babes in Arms, Little Foxes, Tobacco Road, Ah, Wildness!, Anything Goes, Bury the Dead, to name but a few.

And some of our most important playwrights and composers: George Kaufman, Eugene O’Neill, Lillian Hellman, George and Ira Gershwin, William Sarayoan, Clifford Odets, S.N. Berhman, Richard Rodgers, Lorenz Hart, Robert Sherwood, George Kelly, Maxwell Anderson, Irving Berlin, Marc Connelly, and Moss Hart. Ben drew many of the plays, the authors, directors, producers and one one occasion, a dresser.

Times theatre sage Brooks Atkinson believed that in the American theatre of the 1930s playwrights “began to write thoughtful plays about human beings instead of stereotypes.” While the decade has had the reputation for high-minded social drama, there was as much frolic as there was political commitment. If anything the work can be characterized as revolutionary in spirit rather than effect.

Although money was scarce and the country seemed on the brink of collapse, the theatre was in top form, leading critic John Mason Brown (a Solowey subject himself) to refer to the 1930s as “these lean full years.”

The Theatre Guild, which had nurtured many actors and authors in the 1920s, was considered by many to be “the most exciting and responsible” theatre of the time. It continued producing many of the most important works of the day. Porgy and Bess, End of Summer, Mourning Becomes Electra, The Time of Your Life, Mary of Scotland all appeared under the banner of the Theatre Guild. George Bernard Shaw premiered his work in America on Guild stages, and Shakespeare came alive in productions of Twelfth Night with Helen Hayes and The Taming of the Shrew with Lunt and Fontanne.

In 1939 when the Guild produced Phillip Barry’s The Philadelphia Story, Ben was assigned to draw five members of the cast including Katharine Hepburn, a personal favorite. He was warned that she could be difficult, but he like so many performers he discovered “the bigger the people they were, the nicer they were to work with.”

As he recalled later, “About midnight I went with her and one of her co-stars, Van Heflin, to her apartment. I had her sit on the kitchen table for a couple of hours. She offered me a drink and a banana. And she was so pleased with the drawing that she bought it.”

Ethel Merman, Van Heflin, Joseph Cotton, Edith Meiser, Spencer Tracy, Arnold Moss, Theresa Helburn, were among the those who were so enamored with the work they purchased the original charcoal drawing as soon as it was finished. Ben adhered to the same unflinching standards for his commissioned work as he did to his own studio work. Whether the performer was an unknown or a legend, he brought to bear his entire experience up to that point to create a stunning portrait.

An offshoot of the essentially apolitical Theatre Guild was the the ground-breaking Group Theatre who counted among its members Francis Farmer, Luther and Stella Adler, John Garfield, Franchot Tone, and Elia Kazan. Group Theatre co-founder Lee Strasberg brought Method acting to American audiences and forever changed the way American actors worked.

The company was eager to present “sharply oriented political plays” as well as vital young talent. Their work provided Ben with fodder for several portraits, from their first production The House of Connelly in 1931 though their most significant plays, Awake and Sing!, Johnny Johnson, and Golden Boy.

Florenz Ziegfeld continued to produce his eponymously-titled Follies and Ben immortalized seven cast members over the years including Fanny Brice in 1933. Ben drew George S. Kaufman, the author of the most hilarious productions of the times, and many of the Great Collaborator’s plays such as The Man Who Came to Dinner, the Pulitzer prize-winning You Can’t Take it With Youand Of Thee I Sing, Stage Door, June Moon, George Washington Slept Here, I’d Rather Be Right, and Merrily We Roll Along. These plays kept audiences laughing when the world outside could make them cry.

Consider the musicals and revues: Pal Joey, Girl Crazy, Fifty Million Frenchmen, Jubilee, By Jupiter, Lady in the Dark, Panama Hattie, The Band Wagon, George White’s Scandals, Walk With Music, and I Married An Angel. Players in all of these productions were set down in charcoal by Ben.

Lillian Hellman was another young playwright whose name is synonymous with the decade. She burst upon the scene with The Children’s Hour in 1934 which garnered no less than four Solowey portraits during its run. Hellman and her plays Watch on the Rhine and The Little Foxes were also subjects for Solowey portraits.

Among the five drawings from The Little Foxes, Ben drew Tallulah Bankhead twice as the lead, a role which made her a genuine star. Ben said, “I didn’t know whether I should even attempt to do her, because hanging on the wall was an elaborate portrait by Augustus John—a beautiful hunk of painting.” He overcame his intimidation and produced a striking portrait, one of four over the years.

It was not unusual for Ben to record almost entire careers in portraits of performers in multiple roles over the decade. Judith Anderson sat for five Solowey portraits over a ten year period; the glamorous Jane Cowl was the subject of six different drawings; Katharine Cornell four. Alfred Lunt posed for one portrait alone and in four others with Lynn Fontanne, his wife and greatest scene partner.

Walter Huston was seen in four Solowey portraits, one of which he signed “This is the Best yet.” Four of Eva Le Galliene’s characters were preserved by Ben’s charcoal. And Cornellia Otis Skinner, best known for historical monologues The Wives of Henry VIII and The Empress Eugenie had Ben render a portrait each time she created a new work.

Although Ben referred to his Portraits from the Performing Arts as Theatre Portraits, they encompass much more than the denizens of Broadway. In the late 1920s and early 1930s films some studios were still located in New York when Ben arrived. Ben managed to capture the end of the great silent film era as well as the dawning of “talkies” in a series of portraits from the world of film.

Clara Bow, Frank Capra, Marlene Dietrich, Al Jolson, Shirley Temple, Jean Harlow, Ralph Bellamy, Barbara Stanwyck, Claudette Colbert, Bruce Cabot, Lily Damita, Dolores Del Rio, Ronald Colman and early screen heartthrob Lou Tellegan were all subjects of Solowey portraits.

It was the Golden Age of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, with impresario Gulio Gatti-Casazza was responsible for bringing some of the finest voices in the world to this country, and Ben brought them to newspaper readers. Ezio Pinza, Madam Schumann-Heink, Lucrezia Bori, Lawrence Tibbett, Lily Pons, Grace Moore, Edmund Johnson, Leon Rothier, and Arturo Toscannini were all faithfully recorded by Ben’s work.

When assigned to draw Amelita Galli-Curci, one of the era’s most celebrated divas, Ben recalled “I was startled to discover that she had a huge goiter. She said ‘Forget that potato.’ Fortunately when necessary, an artist can arrange instant surgery.”

Besides Broadway hoofers like Ray Bolger, Ben brought the innovative individuals of the dance world to his audience in his portraits of George Balanchine, Vera Zorina, Eugene Loring and Tily Losch.

Ben brought this aspect of his life and career to a close in 1942 when he and Rae moved permanently to Bedminster, in Bucks County, Pennsylvania to a farm they had purchased six years earlier. He still continued to participate in national and international exhibitions and remained a highly-regarded portraitist, but readers never again woke on a Sunday morning to see a Solowey in the pages of their paper . His legacy can be seen in public and private collections around the world and at The Studio of Ben Solowey.